Why we need responsive policies to achieve a rapid energy transition

On 31.05.2020 by Alejandro Nunez-JimenezBy Alejandro Nuñez-Jimenez

Because we are bad at predicting, slow at changing policies, and the stakes are too high. Responsive policies can help to overcome these limitations.

Energy transitions are often assumed to be lengthy, multi-decade affairs. But they do not have to be. Even Vaclav Smil, perhaps the world’s foremost thinker on energy, concedes that regional and national transitions can be very fast. In the current energy transition, policies could determine the pace of change.

Among the tools that accelerate the diffusion of clean energy technologies, few instruments boast a more successful track record than feed-in tariff (FIT) policies. And yet FITs are a perfect example of why the global energy transition could remain slow without responsive policies.

Feed-in tariff basics

Feed-in tariffs are economic incentives to make costly, novel power generation technologies attractive to investors. A FIT establishes a guaranteed price for the electricity fed into the grid by a power generator—typically a fixed rate per kWh above market prices—for a long period of time (e.g., 10-20 years). FITs are one of the most effective tools to reduce investment risk and accelerate the diffusion of energy generation technologies.

Together with rapid cost reductions, FITs are largely to credit for the fast growth of renewable energy. Since 1998, countries, states and provinces using FITs multiplied ten times to reach a total of 111 by 2018, while the cumulative installed capacity of solar photovoltaics and wind energy grew by x1000 and x55, respectively.

Despite being fairly successful at accelerating technology diffusion, FITs are in retreat as competitive auctions and other policies take over. Part of this decline can be explained by the natural progression towards more market-reliant instruments as the PV and wind energy technologies mature. But part of it is also due to the struggles many countries faced while using FITs.

Bad at predicting, slow at changing policies, and facing high stakes

As economic incentives, such as FITs, boost the adoption of technology, learning effects typically reduce technology costs. Sometimes by a lot. The cost of electricity from PV and wind energy has plummeted thanks to technology costs decreasing over 20% for PV and 10% for wind energy per doubling of cumulative installed capacity.

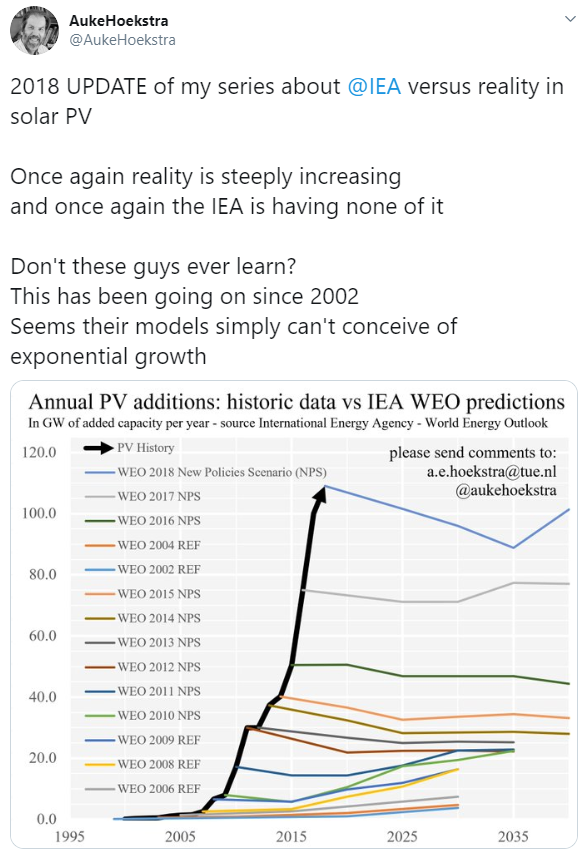

Most analysts (and governments) failed to predict such rapid cost declines, which led them to underestimate, sometimes comically, the speed of diffusion of PV and wind energy.

However, at the same time, as technology costs fall, if incentives are not adjusted, investors can often reap windfall profits. These not only erode the policy’s cost-efficiency but create an urgency to strike while the incentive is hot. To stop the bleeding of public funds, governments need to reduce incentives promptly but they are usually too slow.

Take the case of my home country, Spain, as a cautionary tale.

The generous FIT introduced in June (but published in May) 2007 introduced a mechanism to trigger a “manual” revision of incentives after 85% of the deployment target was reached. The threshold was reached in June 2007. A new, lower incentive was drafted in September 2007 but not passed into law until September 2008. A whole 12-months delay in which over 2,500 MWp were installed (from a starting total of ~300 MW), locking Spain into decades of billions of euros of annual policy costs.

Eventually, the burden became so heavy that Spain dropped the FIT for PV entirely, leading to a lost decade with little renewable energy additions. Similar stories occurred in Italy, the Czech Republic, and even in Germany, where only compulsive policy-making managed to curb policy costs.

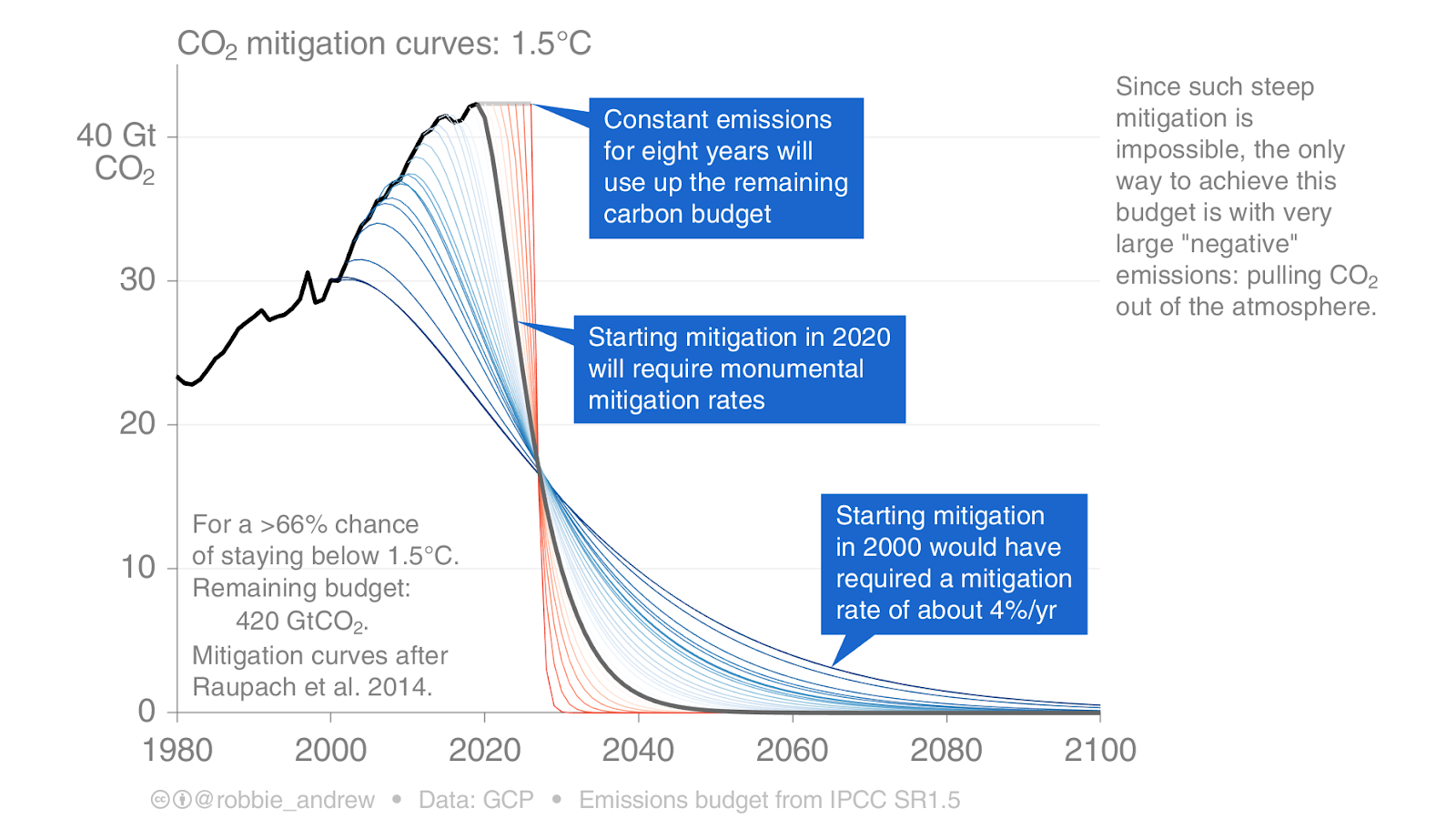

Economic incentives are effective, but because they can become costly, it is tempting for countries to steer clear of instruments like FITs.But we don’t have time to try second-most-effective options, when it comes to accelerating the diffusion of emerging clean energy technologies, such as for storage or electric mobility. Every passing year, the stringency of the CO2 reductions required to limit climate change increases. The COVID-19 crisis has revealed that drastic behavioural changes have modest impacts on emissions. What matters is decarbonizing power generation and surface transportation as fast as possible, and that will require subsidies in one form or another.

Three ways more responsive policies can help

But subsidies don’t have to mean ballooning costs. Instead of reinventing the wheel, let’s make a good tool better. One promising path is to make policies more responsive by introducing elements in their design that increase their ability to react to changes in the context in which they operate. For instance, more responsive policies could help overcome the limitations of the old FIT designs in three ways.

Instead of setting incentives based on predictions for diffusion and prices, responsive policies react as adoption and prices evolve. This can be done by introducing automatic adjustment mechanisms (e.g., akin to the EU ETS Market Stability Reserve instead of a carbon price floor). Instead of taking months to pass new laws, responsive policies adjust incentives as fast and frequently as needed. For example, by triggering changes in incentives when policy milestones are reached – like California and other countries did for solar incentives. But, most importantly, instead of over- or under-shooting their targets, responsive policies would be much more accurate and certain to reach their goals. For instance, by linking adjustments in incentives to the distance to policy targets – as I explored in a recent paper.

In this open-access paper, my co-authors and I investigated how one responsive design for a solar FIT in Germany would have done compared with the historical policy. The simulations paint a clear picture: Germany could have saved over €320 million (−11.7%) per GW installed while reaching its goal with over 90% chances. A second paper (under review), confirms the previous results for Spain and Switzerland, suggesting that responsive designs could work well in different geographies. This is paramount because, for a fast, global energy transition, countries all over need to replicate the fast transitions at regional and national scales.

We can be certain that there will be more shocks during the energy transition. Future policies need to be designed to withstand them. However, responsive policy designs are not a panacea to the risks of economic incentives. Non-economic barriers, such as lack of knowledge about a technology, require complementary tools to avoid unnecessarily high incentives, and carefully crafted legislation is needed to prevent strategic behaviour by investors. But the potential of responsive designs warrants closer inspection by researchers and practitioners. A fast energy transition should not be held back because of our poor prediction skills and slow policy changes. The stakes are simply too high.

Cover photo by Fabien Bazanegue on Unsplash

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: Nuñez-Jimenez, Alejandro. “Why we need responsive policies to achieve a rapid energy transition”, Energy Blog, ETH Zurich, June 1, 2020, https://blogt.ethz.ch/energy/responsive-policies/

If you are part of ETH Zurich, we invite you to contribute with your findings and your opinions to make this space a dynamic and relevant outlet for energy insights and debates. Find out how you can contribute and contact the editorial team here to pitch an article idea!

What is really needed is a price on CO2 emissions and incentives for privates to change to readily available alternatives for coal, oil and gas. Like in Sweden where district heating is the dominant form of heating in cities and where district heating does not use any fossil fuel. Another positive example is Tesla and their electric cars. Within 10 years the price of electric cars of a given range and performance halved – and this is due to a combination of ambition of a private company (Tesla) and financial incentives which lower the price of buying an electric car.

FeedIn-Tariffs for Solar and Wind are indeed very effective when to goal ist more electricity from solar and from wind – but is not very effective if the goal is less emissions from coal, oil and gas. Germany ist the best demonstration for this. Today more than 40% of germans electricity comes from solar and wind, but Germanys CO2-emissions are still very high and Germany even plans to build a brand new coal plant – namely Datteln 4. On the “Datteln 4 Website” of Uniper you read: “The new Datteln 4 power plant will be one of the most modern hard coal-fired power plants in the world. It is designed as a monoblock plant with a gross output of 1,100 megawatts and a net efficiency of over 45 percent. In addition to electricity for public supply, Datteln 4 will be able to generate traction power and supply around 100,000 households in the city and region with environmentally friendly district heating through combined heat and power generation. Datteln 4 is designed for rapid load changes. This high flexibility makes the power plant a reliable partner for renewable energies.”

Not solar and wind in combination with fossil power plants as compensation for dark lulls is the solution, but an energy system which does not rely anymore on coal, oil and gas is the real solution.

Dear Martin,

Thanks for reading my post and for your comment.

I agree with your first point. Both carbon pricing and economic incentives can help diffuse new technologies to reduce fossil fuel consumption, and, thus, CO2 emissions. My contribution in this post deals with *how* those policies should be designed. I have tried to argue why making these policies more responsive can help to overcome the poor predicting skills most analysts show, the lengthy process to change laws and the uncertainty about the policy outcomes.

On your second point, it seems unfair to me to burden the FIT in Germany with the task of transforming the whole power generation mix in the country. Perhaps you would agree with me that the decision to phase-out nuclear power plants has had some influence on the slow decline of CO2 emissions from electricity in Germany. That Germany is inaugurating a coal power plant is a shame. However, neither the decision regarding nuclear power or the fate of coal plants are directly linked to the FIT. In terms of diffusion of solar and wind, the FIT did its job in Germany.

I cannot but wholeheartedly agree with your closing statement.

Thanks again and best regards,

Alejandro

Interesting post, Alejandro. I couldn’t agree more. What is important to consider here are the different institutions in different jurisdictions which may accelerate or hamper responsive policy design. In the early days of the German FiT, the tariffs were prescribed in the law which meant that the parliament had to decide on changes of the tariffs (besides the implemented “Absenkpfad” which was too conservative in its cost reduction estimates). This meant that the entire parliamentary apparatus first had to be set in motion – including lengthy debates – before amendments could be made. In Switzerland, on the other hand, the tariffs were defined in the ordinance and were thus the responsibility of the government which could take much faster decisions. I think such aspects are important to consider in future research.

@Martin Holzherr: A CO2 price is certainly necessary. However, as Alejandro has pointed out, this does not undermine the importance of effective policies that support the deployment of renewable energy technology. The different policy instruments are complementary and we need an effective mix that supports action at all levels.

Dear Léonore,

Thanks for reading the post, and for your comment. I think you raise a critical point that is often neglected. I could not agree more.

The institutional framework underpinning the policy instruments bears a major influence on their performance. More responsive designs could facilitate a quick and commensurate reaction to changes in the context of the policy but they would still require an institutional actor with some independence and discretion to govern the policy. From my simulations, we learned that there could be instances when a responsive design suggests a drastic cut of a subsidy (e.g., a feed-in tariff) or a sudden increase of a tax (e.g., a carbon price). This presents both an opportunity, to compensate for the unavoidable shortcomings of any mechanism prescribing policy adjustments based on a few variables that lack the contextual knowledge a human decision-maker has, but also risks, when those adjustments may be indeed appropriate to maintain the policy’s effectiveness or cost-efficiency but politically untenable. The EU ETS is perhaps a good example.

A very relevant comment that I will keep in mind!

Best,

Alejandro

Great and well-researched post. Impressive!

I support the general message.

Yes, transition policies should be designed in a flexible, responsive way as to react to (yet) unknown developments. And yes, watching out for policy costs is also important.

However, I was wondering whether the focus on a responsive incentive level (e.g. for FITs) isn’t too narrow. Unfortunately, we have seen many other unwanted effects of transition policies in the past. For example i) societal acceptance (local resistance against large scale projects), ii) environmental ‘problem shifting’ (child labor for cobalt for EV batteries, biomass monocultures, unaccounted GHG emissions), iii) X-sector effects (food vs biofuel controversity), iv) bottlenecks in technology development and diffusion (grid expansion, PV silicon crisis) etc.

Don’t get me wrong. All these are ‘normal’ in the sense that things can go wrong if we try something new. Knowbody nows everything in advance and expert predictions often fail, as you rightly point out.

I guess my point is that we need broad ‘policy learning’ or responsiveness to address the uncertainties of transition processes.

Dear Jochen,

Thanks for reading my post, and for leaving a comment! I am glad you enjoyed it.

The topic of this post (and the research behind it) is indeed very narrow. It deals with one element design of one particular (kind of) policy, it can hardly get narrower than that! I also would not claim that more responsive policies would solve any problems beyond their immediate influence.

To your comment, I agree that broad policy learning and responsive is desirable to confront the uncertainties in the transition to sustainability. I guess it would involve changes in the policymaking processes beyond the scope of this post (and my expertise to comment on them). I would only mention one warning. Responsive mechanisms that can apply changes to a policy in a semi- or fully automatic fashion (as the ones I studied in my papers) can raise concerns about responsibility and accountability. My personal view is that policies can become better by becoming more responsive but the process of adopting these mechanisms needs to be reflexive and judicious.

Best,

Alejandro