Understanding the Scale of Back-up Generation in the Developing World

On 06.11.2019 by Yael BorofskyBy Yael Borofsky

Thanks to unreliable electricity grids, fossil-fuel powered generators in low- and middle-income countries constitute as much generation capacity as up to 1,000 coal-fired plants, finds a new report from the IFC and the Schatz Energy Research Center. That sounds bad for the climate and public health, but generators also help people stay out of poverty…

Driving down a mountain in the Swiss Alps after an exhausting late Fall hike, we were hungrily anticipating a good meal, but when we got to the first town and looked around, all the lights were, surprisingly, out. Every restaurant was either completely dark or the tables sported a few flickering candles and a collection of confused looking guests visible through the windows.

None of these businesses appeared to have a back-up power supply, and why would they? This outage was an anomaly — the grid in Switzerland is more than 99% reliable. But what about countries where power outages are the norm?

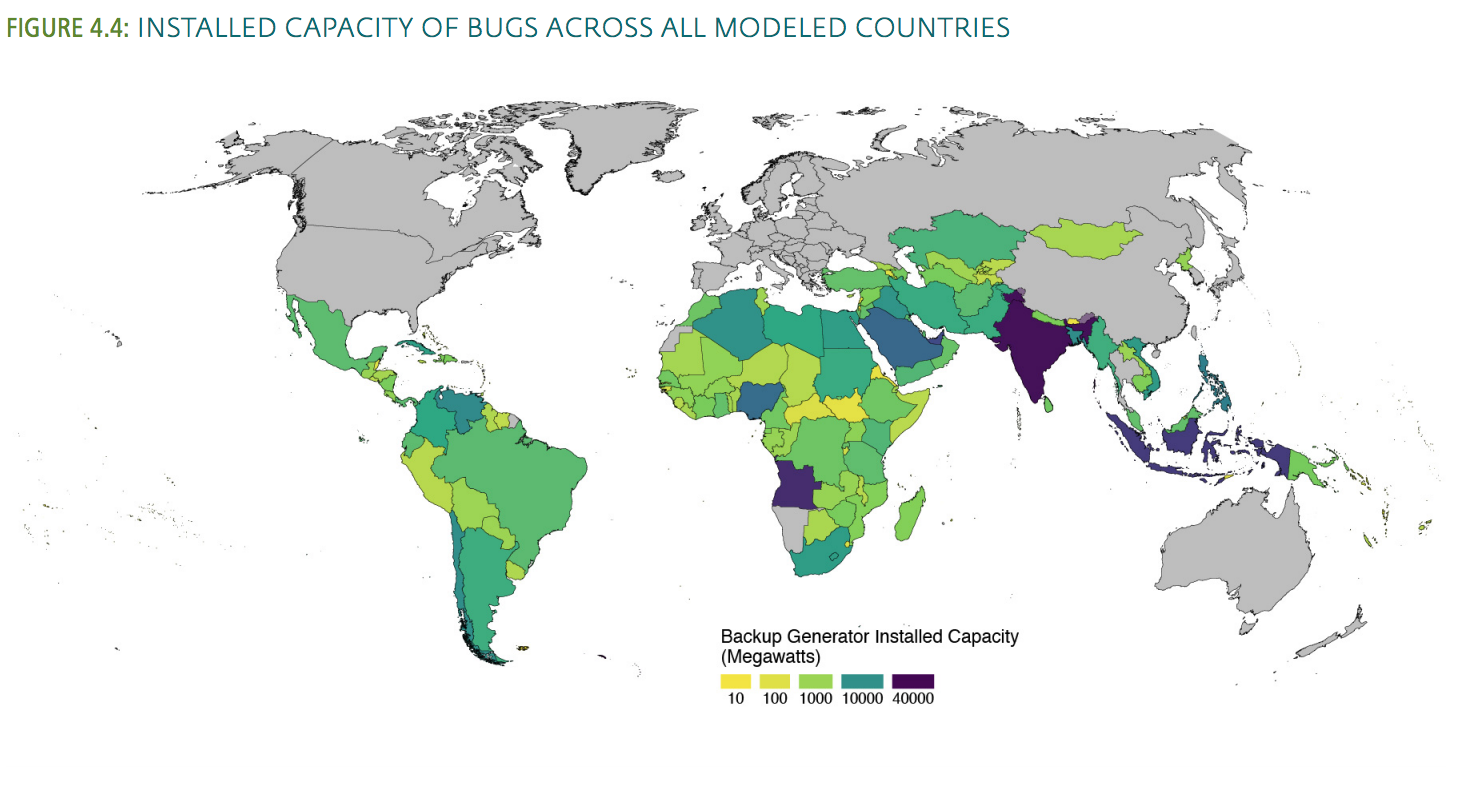

A new report by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) developed in partnership with the Schatz Energy Research Center has found that there are about 350 – 500 GW of back-up generation capacity in low- and middle-income countries — that’s more than 17 times the installed generating capacity of Switzerland, or, as the authors point out, about 700-1000 coal-fired power plants.

The report, “The Dirty Footprint of the Broken Grid: The Impacts of Fossil Fuel Back-up Generators in Developing Countries,” estimates that around two billion people live with more than 100 hours worth of power outages per year (and one billion with more than 1,000 hours per year). In response, many turn to diesel or gasoline generators to keep the lights on and businesses running. The authors set out to model the sheer scale and cost of the back-up generation used to meet all that pent-up electricity demand and the problems that go along with reliance on this technology.

Figure 1: Source: International Finance Corporation, 2019. The Dirty Footprint of the Broken Grid: The Impacts of Fossil Fuel Back-up Generators in Developing Countries.

The report is worth discussing here for a couple of reasons.

First, the report is based on findings from a rather impressive modelling exercise, given the substantial limits to data availability. The authors do a nice job explaining how the data limitations influence the model results. Specifically, they make clear that while the numbers may be underestimates, these results can still inform technology and policy solutions.

Second, the vast majority of work focused on energy access in developing countries zeroes in on households that are not connected to the grid. This report, however, suggests that unreliable grid connectivity is about as big a problem in terms of people affected. These findings raise important new questions about the relationship between energy access and environmental challenges, such as climate change and air pollution mitigation.

So let’s dig a bit deeper into the report.

The Run-down

Using global import and export trade data from 167 low- and middle-income countries (excluding China due to data limitations), along with data on power outages, and generator manufacturer data (primarily from Western manufacturers), the report estimates the characteristics of the back-up generation market. Here are the main findings:

- Roughly 25 million back-up generators were deployed in 2016, and about 75% were used in areas with grid access. For perspective, they point out that the amount of back-up generation in sub-Saharan Africa is almost equal to the installed capacity of all the grid-connected power plants in the region.

- These generators consume about 55 billion liters of diesel and gasoline annually.

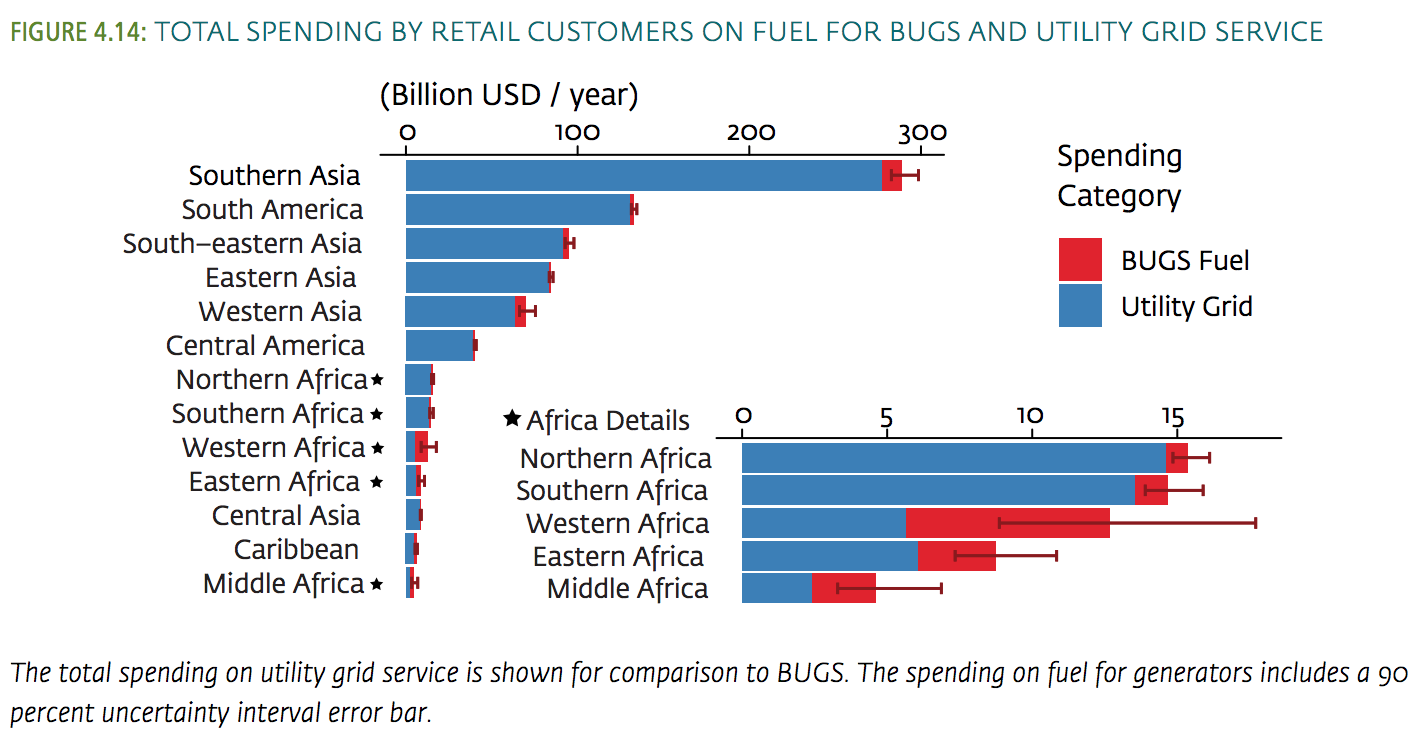

- Collectively, as much as $50 billion is spent annually on fossil fuels for back-up generation. They estimate that this level of spending rivals spending on electricity from the grid in many countries.

- These generators emit approximately 100 megatons of CO2 annually (about 1% of emissions from all modeled countries).

- Generators emit a host of other pollutants that can negatively affect human health and/or are climate forcers, including nitrogen oxides (NOx), fine particulate matter (PM2.5), local black carbon, ozone (O3), and sulfur dioxide (SO2). Emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) account for most of the power sector emissions in the study countries.

Energy Policy for Back-up Generation

So what do we learn from this? For starters, it seems fair to say that generators are primarily being used as a back-up power supply rather than as an alternate means of electricity access by people without a grid connection. That means a large amount of generator usage is not only dirty, it shouldn’t be necessary, but for grid unreliability.

The report argues that this inefficiency represents a serious lost opportunity to channel that money toward grid improvements to increase reliability. What’s worse is that many of the study countries have substantial fossil fuel subsidies in place that further incentivize people to use generators. All of these findings highlight that back-up generation may have a big influence on the dynamics of the electricity sector in low- and middle-income countries, but we still know remarkably little about it.

Figure 2: Source: International Finance Corporation, 2019. The Dirty Footprint of the Broken Grid: The Impacts of Fossil Fuel Back-up Generators in Developing Countries.

The report’s clear take-home message is that clean energy options, particularly solar with storage, are cost-competitive and should replace most diesel and gasoline generators in countries with unreliable grids. Even with the data gaps, they argue that this conclusion is robust given the high estimated costs and the negative externalities associated with fossil fuel-based back-up.

I’m inclined to agree, but what is still missing from this discussion is an assessment of the costs of living with an unreliable grid and without back-up generation. In energy speak, what is the cost — to people, to livelihoods, and to the broader economy — of unserved energy. Those costs must be large if people are willing to spend so much on generators, purchasing fuel and tolerating pollutants that negatively affect their health.

While generators undoubtedly pose problems for individuals and society, they also solve the costly problem of going without electricity in the middle of a work day or during prime cooking hours. Despite all of the drawbacks of generators, they fill what is clearly an immense and under-acknowledged need. Future work will need to consider these benefits more fully in order to affect policies that can drive both grid improvements and incentives for clean energy back-up alternatives.

Back-up Generators, Energy Access, Climate Change, and Health

When we launched this blog, our first post mentioned the tension between ensuring that the roughly one billion people on this planet who lack access to modern energy gain access without exacerbating climate change. This report brings new insight to that discussion, as well.

First, it highlights that when we think about energy poverty, we need to be thinking about and planning for at least another few billion people, since those with unreliable access to the grid are also energy poor.

Second, the report raises important questions about technology alternatives and investment trade-offs. The authors argue that people waste valuable time managing the operation and maintenance of generators, pointing out that for “business operators, this means less time to focus on core income-generating activities.” But it seems that the opposite is also true — without back-up generation those same business owners would not have consistent, reliable power with which to earn an income and avoid extreme poverty.

In other words, in the short term, people’s lives are probably better for using generators, but the long-term environmental and economic consequences of this usage could be better addressed by technology and policy. For example, applying the money from fossil fuel subsidies to clean energy options, like some combination of solar and storage, could at least provide an alternative and limit the underwriting of a technology with major health and environmental impacts. This solution echoes policy conclusions from research here at ETH, which found evidence that rural Kenyans who got access to a solar light replaced their kerosene lanterns roughly one for one. The same study also found that demand for solar is very price sensitive. Thus, subsidizing solar lights and phasing out subsidies for kerosene could help minimize the negative environmental and health externalities of kerosene (full disclosure: I worked as an RA on this research).

In addition, more work could be done to understand what other options exist in both the short- and medium-term. Building on this report, the IFC itself appears to be actively supporting more research on and development of solar-powered alternatives. So is the Access to Energy Institute (A2EI), a non-profit R&D-focused organization, which published a report exploring the potential for solar-based alternatives for back-up generation in Nigeria this summer.

This work is necessary, but there is something to be said for pursuing a broader range of research goals that also include more effective investment in grid management and maintenance or other means of ensuring affordable, reliable electricity sufficient to power both homes and businesses. While reducing carbon and other emissions from fossil fuel consumption is an urgent goal, it should not be at the expense of those with the fewest options.

The full report can be found here.

A summary of the findings from the authors can be found here.

Cover photo by A. Jacobson. Source: International Finance Corporation, 2019. The Dirty Footprint is the Broken Grid: The Impacts of Fossil Fuel Back-up Generators in Developing Countries.

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: Borofsky, Yael. “Understanding the Scale of Back-up Generation in the Developing World”, Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich, ETH Zurich, November 6, 2019, https://blogt.ethz.ch/energy/back-up-generation-developing-world/

If you are part of ETH Zurich, we invite you to contribute with your findings and your opinions to make this space a dynamic and relevant outlet for energy insights and debates. Find out how you can contribute and contact the editorial team here to pitch an article idea!

Leave a Reply