Renewable energy projects take longer to commission than a decade ago

On 06.05.2024 by Anurag GumberBy Anurag Gumber

Anurag Gumber is a doctoral researcher at the climate finance and policy group at ETH Zurich. His interest lies in infrastructure finance. He believes that shaping our physical environment sustainably and appropriately managing risks is the solution to several developmental problems, including climate change. To this end, in his research, he examines how financial policy can accelerate the maturity of new energy technologies, how investors, particularly banks, can gain confidence faster, and how the development processes can be accelerated for new technologies. Prior to joining ETH, he worked for over 7 years in industry as a project developer, transaction advisor, and policy researcher, in countries spanning Africa, Asia, and North America.

The time to commission and install new renewable energy projects has increased over the past decade. In short, we are building slower. Here, we explore factors that have affected timelines and suggest how to accelerate climate action.

Renewable energy is now central to the decarbonization plans of almost every country. The strategy is simple: build new renewable energy projects to replace old, polluting fossil fuel assets. But building new projects takes time and therefore, decarbonization success within the targeted short span of time requires a) building quickly and b) building a lot at the same time.

We typically hear a lot about the latter – building a lot, either in the form of several project announcements or with the announcement of bigger and grander projects which eventually add a big chunk of capacity once they are commissioned. To this end, we also often track goals with cumulative capacity installed, in absolute terms, or as a fraction of total energy consumption. While these achievements are a must to track climate progress, they scarcely discuss a key element – how long these projects take to come online.

Why study project timelines

This scarcity of research investigating “how long” results in unintended policy consequences. First, we don’t know whether the current decarbonization plans devised using complex energy models are realistic about how fast we can install new projects. An underestimation of how fast projects can be practically developed results in highly optimistic models and therefore unrealistic policy goals. This also potentially underestimates the policy support that is required in the long-term. For example, Switzerland’s recent subsidy support for Alpine PV projects lasts until 2025 even though it is unlikely that projects will be submitted, let alone constructed, in that time period.

Second, we don’t know whether financial policy, such as subsidies, is adequate to plug the financial gap to make new energy projects attractive for investors. For simplicity, let’s take an example where a new project costs 10 million and generates an annual return of 1 million over 20 years once constructed. If the project is built within 1 year, the financial return (or internal rate of return, IRR) to the project is 7.75%, whereas if it takes 2 years (assuming cost is equally split over two years), the return drops to 7.3%. If it takes 3 years, the return drops to 6.9% (see the squares in Figure 1). So, imagine if a policy were trying to provide an investor with a subsidy to give a return of 10%, the subsidy itself would cost the government ~700K more if the project took 3 years instead of 1 year (bars in Figure 1). A corollary of the above, and the third consequence, is higher prices that will be passed on to the consumers, either as taxes if projects are subsidized, or as higher charges if not. Although true financial returns range between 5-10% in Europe and North America, and often higher in emerging economies, the above example conveys the financial burden that is added from longer timelines.

Figure 1: Financial return and subsidy for a hypothetical project

Timelines have increased over the past decade

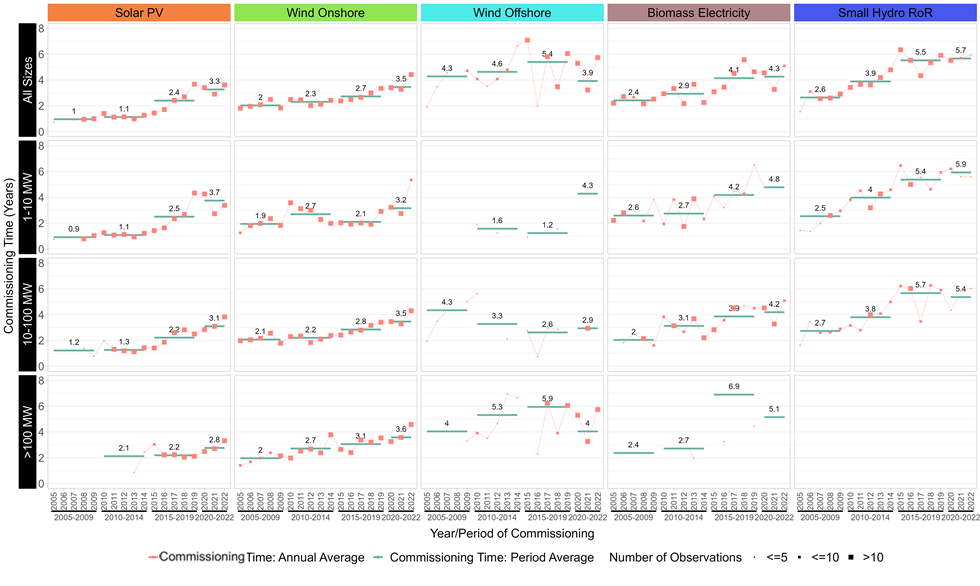

Accordingly, to plug this gap in research, we undertake the most extensive study ever. We examined 12,475 renewable energy projects commissioned in solar PV, wind onshore, wind offshore, biomass, and small hydro run-of-river (RoR), in 48 countries in Asia, Europe, and The Americas, between 2005 and 2022. This data collection and analysis address the two research gaps previously mentioned; firstly, we analyze the historical trend of project commissioning time, and secondly, we identify factors that affect the commissioning time. Although commissioning time represents only one of the three stages of a projects’ deployment with the other two being planning, and permitting, the commissioning time is the longest that warrants attention.

Remarkably, we find that projects take longer to commission than they did a decade ago (see Figure 2). While a natural argument is that time would increase because we build larger projects, the increase we find holds regardless of project size. Among the five energy technologies we analyze, we find installation time to increase the most for biomass and small hydro, followed by solar PV. Between OECD and non-OECD countries, we find solar PV, wind offshore, and biomass to take a shorter time in non-OECD countries. Additionally, among the 48 countries, we find that the majority of countries exhibit an increase in commissioning times between 2015-19 and 2020-22, with 2020-22 marking the effects of Covid-19. 20 of the 30 countries in the data exhibit an increase for solar PV; 28 of 39 for wind onshore; four of seven for wind offshore; three of five countries for biomass electricity; and one of eight countries exhibits an increase for small hydro RoR. Details for each country can be found in the paper under Table F.1.

Finally, among the factors we examine, we find that the commissioning time shrinks as technologies mature. That is, the longer a technology is around in the market, the shorter its commissioning takes. We also find that commissioning time reduces as firms gain experience, but increase with size, public ownership, higher coordination requirements between financial institutions, concurrent and projects built density within a particular area, and macroeconomic shocks (2008 financial crisis or Covid-19).

Implications for policy and research

The outcome of our research serves policymakers and those interested in future research on climate policy. For policymakers, the first action point is to revise decarbonization plans to include realistic time estimates and amend climate support policies to persist with the revised timeline. Even a slight increase in timelines in model assumption may roll over the speed of renewable energy deployment, thereby accentuating the climate crisis. The next action point is to insulate decarbonization plans and projects from macroeconomic shocks. On the revenue side, this can be done by assuring fixed forms of remuneration either through feed-in-tariffs or two-sided contracts for difference. Over the long term, policymakers should also promote a wide variety of actors who can build confidence in a technology over time. The more experienced actors we have, the more projects we can build faster. This can be done by promoting small and medium enterprises in public procurement and/or auctions.

For researchers, we have much to work on, starting with the revision of energy models that advise policy. Even a 1-2 year difference has the potential for much delay or change in potential pathways as mentioned above. Next, researchers must also go deeper into country– and technology–specific processes that affect the full timeline of a project. Last, since we only study commissioning time, which is a subset, even if a large one, research is needed on examining the time it takes to develop, and permit projects.

Cover image: Greece-China News

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: By Gumber, Anurag. “Renewable energy projects take longer to commission than a decade ago”, Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich, ETH Zurich, May 6th, 2024, https://blogt.ethz.ch/energy/slow-renewable-projects

If you are part of ETH Zurich, we invite you to contribute with your findings and your opinions to make this space a dynamic and relevant outlet for energy insights and debates. Find out how you can contribute and contact the editorial team here to pitch an article idea!