Are Swiss solar PV auctions well-designed and how can they be improved?

On 04.07.2023 by Mak DukanBy Mak Dukan

Mak joined the Climate Finance & Policy (CFP) group in May 2022 as a Postdoc, mainly working on the SWEET EDGE project aimed at accelerating the deployment of renewable energy in Switzerland. His work includes investigating the costs of capital and financing for various renewable energy technologies in Switzerland and abroad. Mak conducted his PhD in Energy Economics at the Technical University of Denmark, where he investigated how auctions for renewable energy support impact renewable energy financing.

Auctions for renewable energy support have become the standard way to give out subsidies to solar energy projects and other renewables in Europe. In an auction, investors usually compete to receive the subsidy based on their offered support price, where the bidders with the lowest offered prices win. The Swiss government has started using auctions to award investment subsidies to larger PV projects. Are the auctions designed well and fit for purpose? How have the auctions performed until now?

The Swiss Federal Ministry for Energy (SFOE) recently completed its first two auctions for solar PV projects. The auctions awarded successful bidders an investment subsidy, covering part of the project’s capital expenditures. Have the auctions been successful? Here I assess the results and discuss how the Swiss auction designs might influence the auction outcome.

Swiss solar PV auctions

Auctions have become the primary means of awarding support to renewable energy (RE) projects in Europe and globally. In an auction, project developers and investors bid to receive government support. Typically, the winners are those bidders offering to develop projects for the least support. In most European auctions, the support includes government payments to the winning bidders – usually a guaranteed price for each kWh of produced electricity or so-called contracts for difference (CfD).

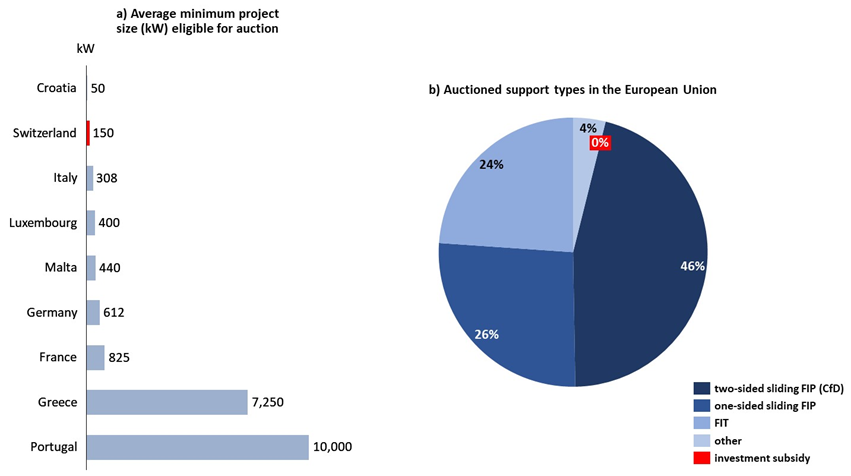

The Swiss auctions are considerably different from other European PV auctions. First, bidders compete for an investment subsidy (covering up to 60% of investment costs), unlike a CfD contract that most EU countries award (see Figure 1b). Second, only projects larger than 150 kW can participate. In contrast, the size limit in European countries with solar PV auctions was significantly bigger, even in smaller markets like Luxembourg and Malta, where PV auctions awarded projects larger than 400 and 440 kW, respectively (see Figure 1a). Third, the auctions were only for rooftop PV projects without self-consumption. Projects with self-consumption and lower than the 150 kW size limit can also receive an investment subsidy covering lower shares of the overall investment. However, such projects do not have to compete for support in an auction.

Figure 1. a) The average minimum size threshold in European solar PV auctions and b) the support type awarded by PV auctions in Europe. Source: AURES II auction database

Despite these particularities, were the two recent solar PV auctions successful? A renewable energy auction is successful if it achieves two things: 1) it creates competition – bidders submit more projects than the government’s auction volume, i.e., the auction is oversubscribed, and 2) it decreases support prices, delivering renewable electricity for less taxpayer money.

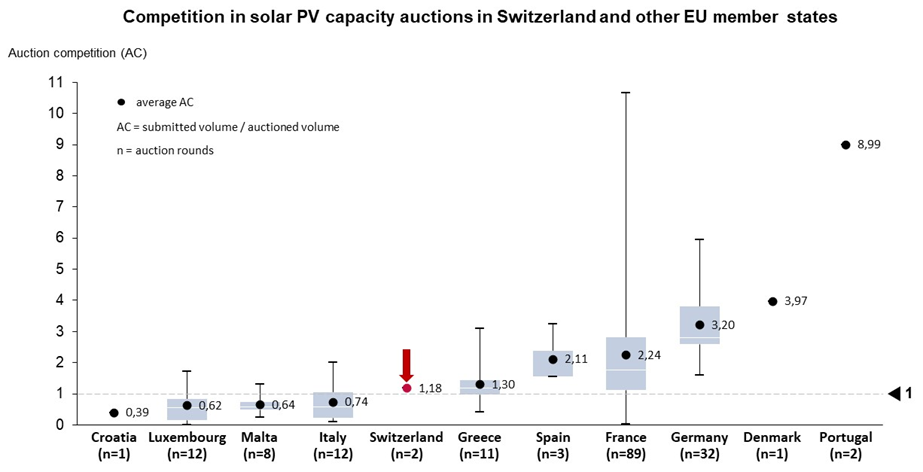

The first solar PV auction was undersubscribed, and out of the 50 MW of auctioned solar PV capacity, SFOE received offers for 43 MW and awarded only 35 MW worth of projects. The second round was oversubscribed with 74 MW worth of bids, of which 47 MW received support. Despite the higher competition, the second round saw an increase in average awarded prices – from 516 in the first to 534 CHF/kW in the second round – moving closer to the maximum allowed bid of 650 CHF/kW. Therefore, on average, the auctions have until now performed “okayish” – better than other smaller markets like Malta, Luxembourg, and Croatia and worse than bigger EU markets, as I show in Figure 2, where I compare auction competition across countries.

Figure 2. Auction competition expressed as MW of submitted bids divided by the MW of offered auction volume. Values lower than one received less bids than the government’s auction volume. Souce: AURES II auction database

The shortcomings of the current auction designs

Switzerland has ambitious climate and energy goals, aiming to become carbon neutral by 2050, mainly by investing in new PV capacities. Achieving this is an ambitious target requiring massive capital investments from various investor types. What could the Swiss government do to improve its PV auctions?

First, there are good reasons why none of the 205 European solar PV capacity auctions were for an investment subsidy covering the initial capital expenditures. RE projects with intermittent production, like solar PV, have two key revenue risks – volume risk, or how much and when they generate, and price risk, or for how much they sell their electricity. An investment subsidy fails to hedge projects against both of these risks. At the same time, a CfD stabilizes the project’s revenues over 15 to 20 years, making them bankable (even conservative banks would finance the projects). Considering Switzerland’s goals to become carbon neutral by 2050, it needs all the Francs it can muster, including low-cost commercial bank debt. The Swiss banks are more or less dormant in financing the energy transition, while in countries like Germany, they are one of the biggest capital providers. Unlike CfDs, investment subsidies do not provide long-term revenue security, making project financing very challenging.

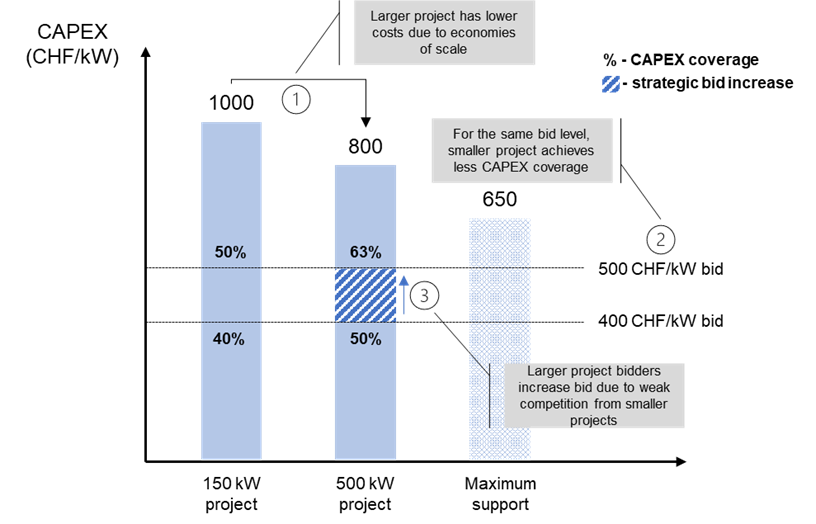

Second, having a 150kW size limit and allowing smaller projects to participate together with larger ones could lead to strategic bidding. Larger PV projects are generally cheaper per kW than smaller projects, resulting in lower investment subsidy needs. The same bid amount can cover a more significant share of capital expenditures (CAPEX) for a larger 500 kW project costing 800 CHF/kW than a smaller 150 kW installation costing 1000 CHF/kW. If larger bidders know their competition is weak – i.e., relatively more expensive – they will intentionally bid a higher investment subsidy, as shown in Figure 3. Even though the 150 kW size limit allows more projects to participate, it could lead to an uneven playing field and more expensive auction outcomes.

Figure 3. The effects of having strong and weak bidders participating in the same auction.

Third, allowing only projects with no self-consumption decreases the pool of potential auction participants. Since the PV tariffs are usually much lower than the regulated electricity prices, self-consumption is a significant driver of profitability for solar PV in Switzerland. Instead of imposing a small size limit to increase competition, the government could reconsider allowing the participation of projects with self-consumption or at least partially covering electricity consumption on site.

Key recommendations to impose Swiss PV auctions

In summary, I see three things the Swiss government can do to improve its auction designs and accelerate the construction of PV. First, enabling projects to compete for CfDs instead of investment subsidies to increase their bankability via larger revenue stability. Second, increase the size limit to at least 500 kW or, as an alternative, organize separate auctions for different bidder groups. Third, broaden the auction participant pool by allowing at least some share of self-consumption. These measures could increase auction participation and lead to better outcomes for the public, including a reduction in bid prices and support costs.

Cover image : Creative Commons Licence https://www.flickr.com/photos/alachuacounty/30529803866

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: Mak Dukan. “ Are Swiss solar PV auctions designed well and how can they be improved? ”, Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich, ETH Zurich, July 03, 2023, https://blogt.ethz.ch/energy/pv-auctions

If you are part of ETH Zurich, we invite you to contribute with your findings and your opinions to make this space a dynamic and relevant outlet for energy insights and debates. Find out how you can contribute and contact the editorial team here to pitch an article idea!