by Grace M. Crain, doctoral researcher, 22 April 2021

“I came to understand that creating resilient food systems is deeply connected to personal relationships; an understanding that applies to humans that occupy this planet, and others we may visit in the future.”

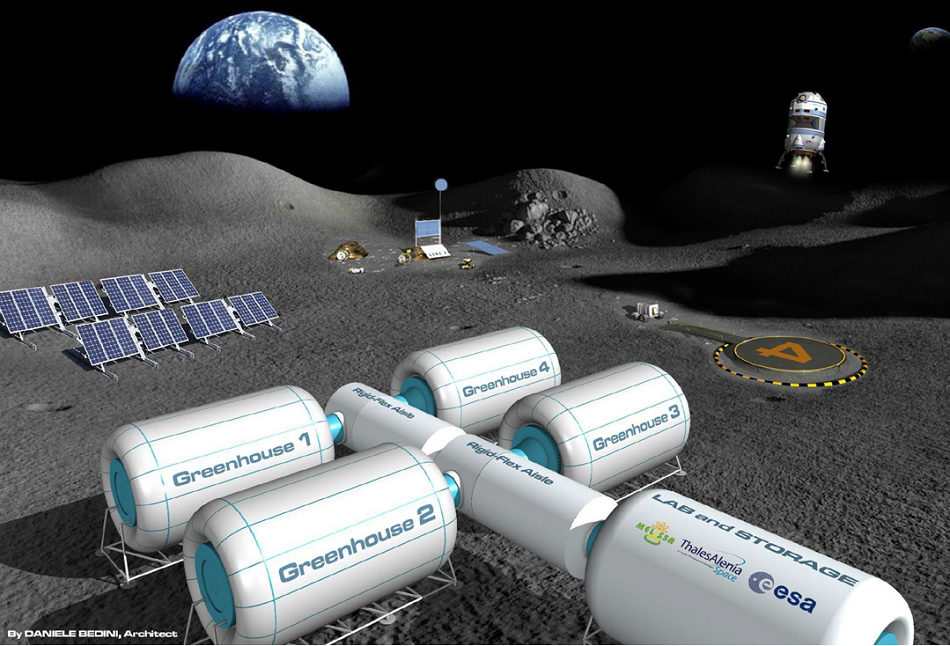

I went into the course on “Creating Resilient Food Systems: A Circular Approach” from the World Food Systems Center (WFSC) with the intention and drive to learn about circular food systems on Earth, since my work is a bit more outside of this world. I work on bioregenerative life supports systems for future space missions. Specifically, I look at how waste can be transformed to provide nutrients for plant production on Martian or Lunar bases. Though the research I contribute to applies to space, the principles have a direct relation to creating and implementing circularity in a terrestrial context. Basically, I am intrigued by the connections that may come up when applying elements of agroecology to bioregenerative life support systems.

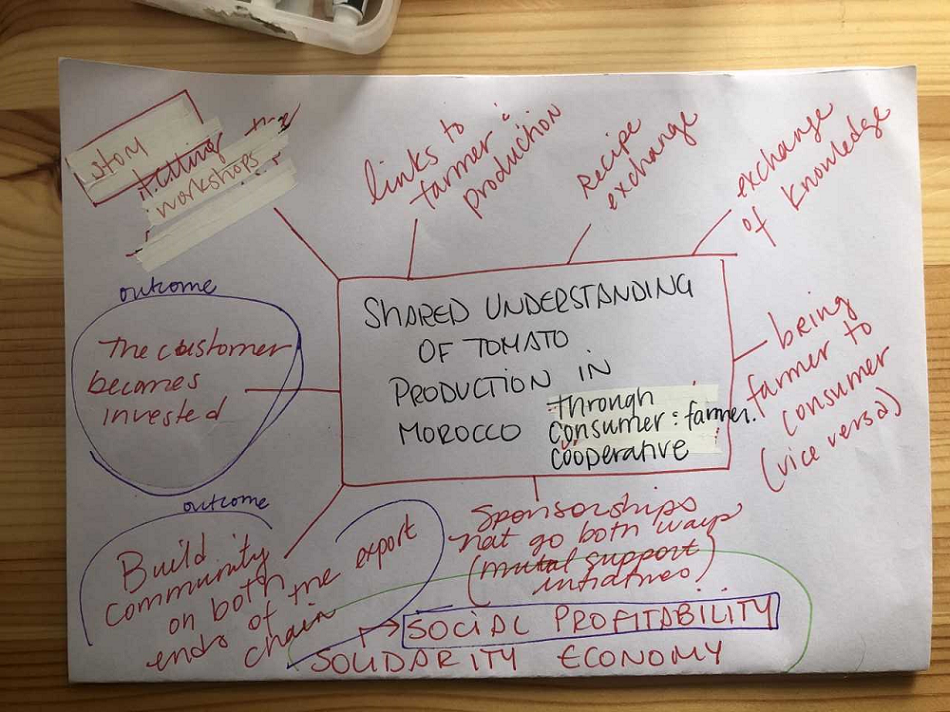

Throughout the three-day course, we heard from agroecologists, data scientists, and political scientists. Additionally, we worked in groups with even more occupational diversity. The group I was in consisted of an artist and urban ecologist, agricultural data scientist, agronomist, a plant scientist and seed collector, and me, an aspiring astrobiologist. In our assigned groups we were encouraged to apply the elements of agroecology, system dynamics, and political ecology/economy to create a more resilient food value chains. Specifically, our group focused on how to integrate the principles of solidarity economy on tomato exports. Basically, how can we shift the focus away from financial profits and more towards social profitability.

At first this was a daunting task, especially for someone so new to the concepts and principles of agroecology. But I remembered this was a learning exercise and way to capture an understanding of these principles and how they can be applied. As a group, we quickly realised that we could approach this from an interdisciplinary perspective, which was what the course ultimately taught me. That to create resilient systems, we must look from multiple perspectives and find the connections between them. We must think in systems. Systems do not follow one principle, path or logic. Systems are a conglomeration of different aspects, that all must be explored. For instance, the farmers tending to the tomatoes have just as much a say as the consumers. To create a resilient system, all sides of the story must be heard and implemented.

We found that, to address our assigned task, our group was missing key perspectives in order to establish a realistic approach. Basically, we had no way of speaking to farmers and incorporating their side of the story. Nonetheless, we were able to approach the assignment from multiple perspectives based on our various backgrounds. We combined our personal experiences with the relationships we as consumers would like to have with farmers and producers to increase solidarity amongst all parties. That is how our group came up with the idea of creating a platform that would connect consumers to tomato farmers through storytelling and shared experiences.

By creating and building personal relationship with the farmers, we believed solidarity and understanding would increase across the entire value chain. With this same principle in mind, I realized how our group connected on a personal level, which allowed us to create an environment of mutual respect and understanding that enabled us to tackle the task at hand. We were able to involve one another and support the evolution of our ideas to create something that we were all proud of and had contributed to. For me, this was the biggest take-away from the three-day course:

I realised that interdisciplinary approaches involving multiple perspectives, looking at entire systems, and listening to all sides of the story are the key to creating circular resilient food systems.

Beyond the example of tomato production, if you consider the context of a bioregenerative life support system, these concepts can also be directly applied. If we don’t pay attention to the entire system and consider multiple perspectives in addressing issues or simply creating the basis on which a system is built, we will fail. For instance, if not enough nutrients are provided to the plant, there will be no food or oxygen production for the astronauts; bioregenerative systems rely completely on the functioning and production of plants. Paying attention to the entire system and looking at all sides of the story is what drives the creation and implementation of resilient, sustainable, and successful food systems for both Earth and Space.

About the author

Grace M. Crain is an aspiring astrobiologist and plant nutrition scientist. She is a doctoral researcher in the Group of Plant Nutrition at ETH Zurich. Grace’s research focuses on determining the suitability of using human excreta for hydroponic crop production for future long-term space missions. Her work contributes to the MELiSSA Project of the European Space Agency. When Grace is not dreaming about space, she is probably out exploring the nearby forest, painting, or playing her ukulele.

Grace Crain (she/her) | LinkedIn