by Shirley Mambadzo, student at Stellenbosch University in South Africa

& ETH Ambassador, 15 April 2021

Online platform

I was awarded a full scholarship to participate in the short course organised by the World Food Systems Centre (WFSC) – Designing for Food Systems Resilience: A Circular Approach, which was held on 10-12 February 2021. It was the first time I had enrolled for an asynchronous international online course and I was nervous. I wondered whether I could contribute in a significant way and whether my internet connection would be stable enough. My anxiety grew more intense because we had to use Miro – an application I hadn’t used before. But when the course started, I realised that I wasn’t the only one new to it, and that gave me confidence. Toya Bezzola, Interim Education Manager at WFSC, helped us navigate the Miro board, and it proved a very useful tool for brainstorming and putting together our group presentation. Michelle Grant, Education Director at WFSC and course facilitator, did an amazing job at facilitating the programme and making sure that everyone was accommodated, ensuring a smooth transition between activities and time-keeping. Speaking of time management, I didn’t know that the Swiss were renowned for being punctual! Fortunately, I don’t have a problem with punctuality and was able to keep to the schedule. The way the breakout sessions and activities were structured allowed me to interact with different participants and to share my story and insights.

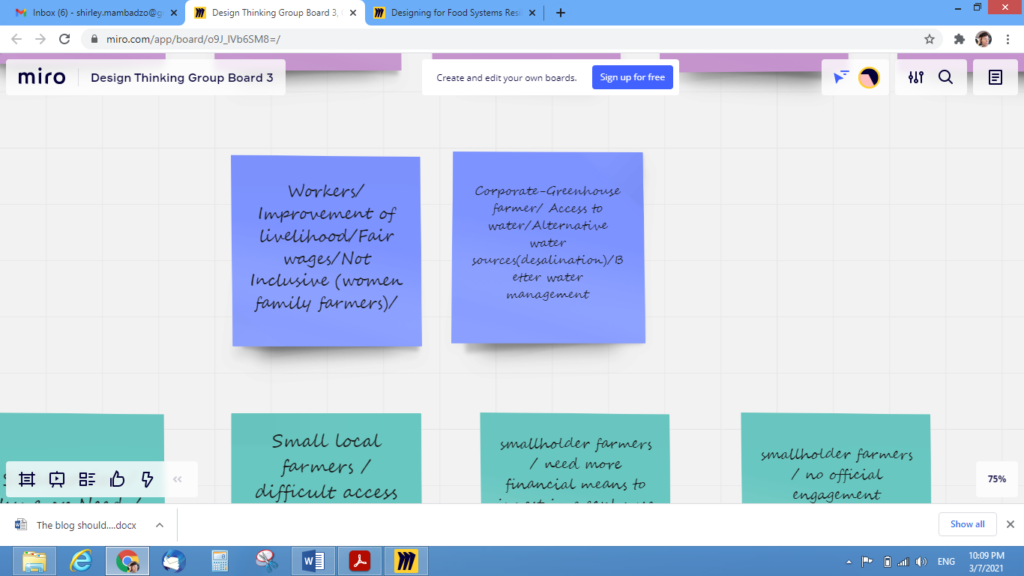

Miro activity: Stakeholder analysis (photo credit: Miro/Shirley Mambadzo)

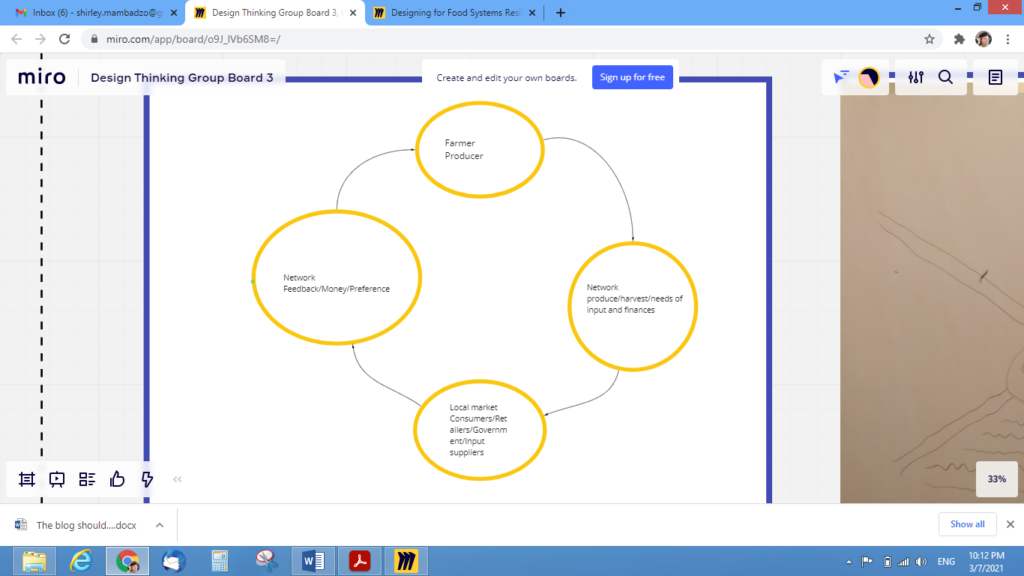

Value chain brainstorming idea (photo credit: Miro/Shirley Mambadzo)

Miro board: Introduction to where I’m from – sunny and rainy Namibia (photo credit: Miro/Shirley Mambadzo)

Group work

We were a diverse group of international participants from a range of disciplines. Although most of those in my group were PhD students or graduates, they took my input for the group project seriously. We had different perspectives, perhaps due to our personal biases, but nonetheless together redesigned a hypothetical Moroccan tomato value chain by integrating the principles of a solidarity economy. Some ideas, especially those on a central governance system made me uncomfortable because of my personal experience and views. To me, this implies that people aren’t capable of governing themselves. After some discussion, I realised that it stems from the trust that the other participants had in their governance systems – which are transparent and mostly well-run.

Feeding free-range chicken barley fodder grown in a hydroponic system (photo credit: Shirley Mambadzo)

Here I am in the plastic covered greenhouse where we grow tomatoes during winter (photo credit: Charles Mambadzo)

Nutritious free-range chicken eggs (photo credit: Shirley Mambadzo)

Course content

I’m really grateful for the knowledge and skills I’ve gained. My biggest takeaway from the course is systems and design thinking methods. As our case study was on the tomato value chain in Morocco, which is also in the global south, there were many similarities with my experience as a part-time farmer/agribusiness entrepreneur and the water scarcity challenges in parts of Namibia, especially the capital city Windhoek, where I work for the local authority. The local authority owns land on the outskirts of Windhoek that is currently underutilised for food production. I intend to use the insights gained through this course to analyse the existing urban food system. However, designing a resilient food system in urban areas using a circular approach is challenging as there’s not enough data on urban food security and the flow of food into and out of the city. Without this critical information, how can we design a resilient food system in the city? This is something I’ll cover in my Master’s thesis and use to improve my current community engagement projects on urban gardening. For some time now, I’ve been testing circularity for my agribusiness: I grow barley fodder in the hydroponics system that we designed, to feed chicken, and then feed the chicken droppings to fish in the aquaponics system, and also plant leafy greens in the aquaponics system. We continuously test and improve, and this is a key element of the reflection stage of the design thinking process as explained by Michelle Grant. I’m looking forward to using the tools in a real-life situation and to seeing what will happen.

Tomatoes (photo credit: Charles Mambadzo)

Tomatoes (photo credit: Charles Mambadzo)

Our aquaponics system where we plant spinach and green peppers (photo credit: Shirley Mambadzo)

Removing dead leaves and checking the system (photo credit: Charles Mambadzo)

Our children in the back garden in Windhoek. We encourage them to join in so that they learn where their food comes from and how it grows. (photo credit: Shirley Mambadzo)

Healthy spinach plant (photo credit: Shirley Mambadzo)

About the author

Shirley Mambadzo works at the City of Windhoek, the local authority of Windhoek, Namibia. She is a part-time agribusiness entrepreneur and student at the Sustainability Institute of Stellenbosch University in South Africa, studying for a postgraduate Diploma in Sustainable Development.