Working in Lesotho

In many ways, the project on molecular HIV diagnostics was a dream come true. The application of biotechnological techniques to improving access to HIV diagnostic services in rural Lesotho, a small landlocked country in southern Africa, has been a chance to draw on and expand my knowledge of molecular biology while gaining exposure to the daily joys, challenges, frustrations and opportunities of working for an NGO in a low-income country. I have been granted the opportunity to work at the intersection of two fields that are rarely combined, but that I feel most passionate about – molecular biology and international development. At the same time, I got to participate in a collaboration between the two geographic regions closest to my heart – southern Africa, where my parents grew up, and Switzerland, where I myself was born and raised.

The goal of the “Towards 90-90-90” research consortium for which I work is to improve healthcare in rural Lesotho, the country with the second-highest HIV prevalence worldwide.

Much of our efforts are directed at reaching the United Nations’ “90-90-90” goals: by the year 2020, 90% of the population should know their HIV status; 90% of the HIV-positive population should receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those on ART should be virally suppressed.

I focus mainly on the last “90” – monitoring treatment outcomes. Much of my work takes place in a seemingly improbable setting: Imagine the rural village of Seboche, reachable only by a somewhat precarious gravel road.

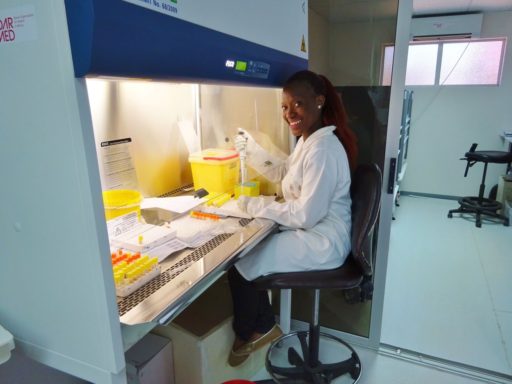

Many people here live without electricity or running water. The village has one rather informal grocery store, a liquor store, and a shack where the staple papa ka moroho (cornmeal with cabbage) is sold by the side of the road. Driving there, I pass “herd boys” tending their cattle, men and women cloaked in the traditional Basotho blanket, and commuters travelling by donkey. Seboche’s distinguishing feature, however, is a 1962 Irish Mission Hospital, a regional hub for healthcare provision and the site of a diagnostic laboratory. It is in this unlikely setting that the nation’s first platform for genetic drug resistance testing of HIV is being set up. The ultimate goal is that an HIV-positive patient’s blood samples can be analysed to reveal the genetic sequence of that individual’s HIV population, thereby identifying any mutations that may render the virus resistant to the antiretroviral drugs the person is taking. This will allow for targeted adaptations of drug combinations for patients whose current drug regimen cannot successfully suppress the virus. The test is routine in high-income countries, but organising logistics and procurement in Lesotho is challenging – not to mention ensuring correct workflows in the laboratory itself. My tasks, then, are to support the launch of these systems, aid in the planning of new laboratory structures, organise procurement from regional suppliers, and train additional laboratory staff in the required molecular biological techniques. In addition, I am planning several research projects, and acting as a link between Swiss and Basotho partners.Living in Lesotho

After eight months in Lesotho, I am reaching the end of my internship towards a Master of Advanced Studies in Development Cooperation. My time here has been intense, motivating, sometimes frustrating, but always engaging. Due to the shear breadth of topics I have had to deal with – and the fact that knowledgeable supervisors, though supportive from afar, where not always easy to reach – I have learned more, and about a broader range of topics, than in many a previous project.

Furthermore, I have met an astonishing mix of local and international residents whose stories are as fascinating as they are diverse. For example, my Mosotho neighbour Thabo, transitioning from nursing to a research career, has one of the most positive personal growth mind-sets I have yet encountered. The Egyptian doctor Mohammed, in Lesotho to increase his knowledge on HIV management, is willing to face serious stigma in his home country to support HIV patients whose very existence the Egyptian establishment is, apparently, unwilling to acknowledge. A number of Congolese medical doctors bring much-needed expertise to the country, while long-term American Peace Corps volunteers work on anything from literacy promotion to women’s empowerment. Finally, my Swiss housemate Alain is conducting clinical research that may well challenge the World Health Organisation guidelines on HIV management in resource-limited settings.

Search for images of Lesotho online and you will find photos of the famous Masked Horsemen, of men and women clad in Basotho blankets, of rolling hills and mountain peaks that render this small country deserving of its monikers as the “Kingdom in the Sky” or, as I am often reminded, the “Switzerland of Africa”. All this is not just cliché – the Basotho are fiercely proud of their nation and traditions, and have developed a strong sense of national identity despite their economic dependence on South Africa, the regional hegemon that completely surrounds this land-locked nation. Indeed, when the draw of the urban world gets too strong, it is easy to hop over the border to South Africa, be it to indulge in such simple luxuries as feta cheese and unsweetened wine, or to see greats like the comedian Trevor Noah perform on his home turf. Either way, my return journey to Butha-Buthe always feels like coming home.

Taking Chances

I want to end on a personal note. Despite the positive terms in which I have described this opportunity, the truth is that I came close to turning it down. The reasons at the time were manifold: uncertainty about the future direction of my career; fear of foregoing PhD opportunities; doubts about the compatibility of molecular biology and development work; and, not least, financial insecurity. The fact that in the end I pushed ahead owes much to the patience and support of those around me, to whom I am deeply grateful. ETH prepares us well for the opportunities that come our way – if we are able to see them.

For my part, after years of straightforward study, I was hesitant to venture so far off the beaten track – in academic rather than in geographic terms. I am glad, though, that I did. I am glad that I took a chance and followed my dream. And if any recent graduate reading this is filled with the same sense of doubt, I would encourage them, enthusiastically, to do the same.

By Jennifer Brown (locally known as Mosa Sootho)

Jennifer Brown, a molecular biologist by training, is currently enrolled in a Master of Advanced Studies in Development and Cooperation (MAS D&C; NADEL) at ETH Zurich. As part of this programme, she is spending eight months in Lesotho, southern Africa, supporting clinical laboratory facilities and working in the field of molecular HIV diagnostics and paediatric HIV research. The project is a joint collaboration of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, the NGO SolidarMed, the Molecular Virology group of the University of Basel, and two hospital laboratories in Butha-Buthe district, Lesotho. Upon her return to Switzerland, she plans on starting a PhD programme in Molecular Virology at the University of Basel, while completing final courses for her MAS.

For more information on the project and partners, visit:

https://visibleimpact.org/projects/1261-molecular-hiv-monitoring-in-lesotho

http://www.solidarmed.ch/de/laender/lesotho

https://www.swisstph.ch/en/projects/lesotho-cascade-trial/