[:de]Informationsfreiheit versus Privatsphäre – ein Innovationsthema für Bibliotheken?[:en]Freedom of information versus private sphere – an innovation topic for libraries?[:]

[:de]Im Oktober 2014 wurde der Friedenspreis des deutschen Buchhandels an den amerikanischen Informatiker, Musiker und Schriftsteller Jaron Lanier verliehen. Die Begründung der Jury: “Eindringlich weist Jaron Lanier auf die Gefahren hin, die unserer offenen Gesellschaft drohen, wenn ihr die Macht der Gestaltung entzogen wird, und wenn Menschen, trotz eines Gewinns an Vielfalt und Freiheit, auf digitale Kategorien reduziert werden.”

Im Dezember 2014 erhielt der ehemalige amerikanische CIA-Mitarbeiter Edward Snowden den Right Livelihood Award “[…] for his courage and skill in revealing the unprecedented extent of state surveillance violating basic democratic processes and constitutional rights”.

Im Mai 2014 entschied der Europäische Gerichtshof, dass Betreiber von Suchmaschinen im Sinne des Datenschutzes dazu verpflichtet sind, gewisse Webseiten aus ihren Suchergebnissen zu entfernen, um das sogenannte Recht auf Vergessen bezogen auf sensible persönliche Daten zu wahren. Europaweit erhielt Google bislang insgesamt 205.724 Anträge zur Löschung von Webseiten. 747.832 Webseiten prüfte Google und entfernte davon 40,4 Prozent. Von den Löschungen waren insbesondere soziale Netzwerke und weitere Suchdienste betroffen. Das Urteil wurde grundsätzlich positiv aufgenommen. Kritiker verweisen jedoch darauf, dass das öffentliche Interesse an bestimmten Personen durch das Urteil massiv eingeschränkt werden kann und jeder Löschung mithin eine gründliche Prüfung durch Experten vorangehen müsse.

Diese medienwirksamen Beispiele der Präsenz des Digitalen führen vor Augen, dass unsere Gesellschaft in verschiedensten Teilbereichen bereits von Möglichkeiten und Grenzen des Digitalen geprägt ist. Die Beispiele zeigen insbesondere auch, dass Gefahren für Einzelne wie auch für die Gesellschaft von den Funktionsweisen des Digitalen ausgehen können. Nahtlose Informationsversorgung, mobile räumliche Navigation, berufliche und private Vernetzung über Social-Media-Kanäle bringen neben mehr Flexibilität potenziell auch mehr Transparenz über individuelle Aktivitäten mit sich. Private Daten werden kommerziell nachgenutzt und die Macht über einmal öffentlich zugänglich gemachte Inhalte im Netz lag und liegt häufig – zumindest bis zum Urteil des Europäischen Gerichtshofs vom Mai 2014 – gänzlich ausserhalb der Kontrolle der Person, auf die sich die Daten beziehen. Sehr eindrücklich weist z.B. der Philosoph Byung-Chul Han in seinem Text Transparenzgesellschaft (Matthes & Seitz 2012, S. 76f) darauf hin, dass in der digitalen Gesellschaft durch die freiwillige Aufgabe von Privat- und Intimsphäre und die damit verbundene Transparenz neue Formen der Kontrolle möglich werden.

Trotz dieser Entwicklungen und Einsichten wächst innerhalb unserer Informationsgesellschaft das Bewusstsein nur langsam, dass der digitale Raum – in seiner aktuellen Form – als quasi “öffentlich” zu begreifen ist und dass Eigeninitiative und Zusatzaufwand erforderlich sind, um die eigene Privatsphäre zu schützen. Oftmals werden persönliche Daten vorbehaltlos – z.B. durch Zustimmung zu nicht gelesenen Datenschutzklauseln oder durch öffentliche Zugänglichmachung in sozialen Netzwerken – zur weitgehend unkontrollierbaren Nachnutzung freigegeben. Der Schutz von schützenswerten privaten Daten kommt dabei häufig zu kurz.

Abb.1: Sayings of DonkeyHotey #002, Flickr, CC-BY-2.0

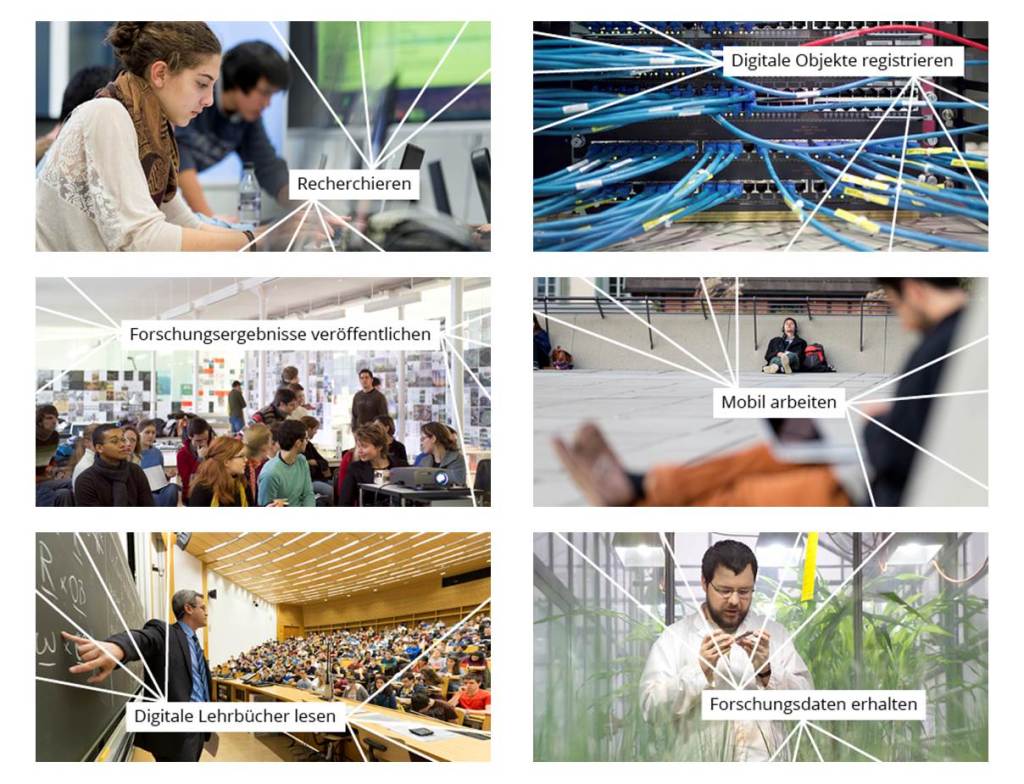

Die Präsenz des Digitalen prägt – insbesondere in ihren positiven und erweiternden Möglichkeiten – auch die Arbeit wissenschaftlicher Bibliotheken. So werden u.a. Publikationen und die den Publikationen zu Grunde liegenden Forschungsdaten zunehmen digital zur Verfügung gestellt und damit für verschiedene Kontexte nachnutzbar gemacht. Auch darüber hinaus bewegen sich Bibliotheken und ihre Kundinnen und Kunden zu grossen Teilen im digitalen Raum.

Damit werden Schnittstellen und systemübergreifende Funktionen von digitaler Authentifizierung und Autorisierung immer wichtiger. Denn diese machen es technisch erst möglich, einen umfassenden und nahtlosen Zugriff auf Informationen zu gewährleisten. Bibliotheken, deren Rolle es ist, in diesem Feld neue technische Lösungen auszuloten, bewegen sich hier zunehmend im Spannungsverhältnis zweier gleichrangiger Grundrechte: Der Informationsfreiheit und dem Schutz der Privatsphäre.

Abb. 2: Beispiele digitaler Nutzungsszenarien bei denen wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken Unterstützung bieten

(© ETH-Bibliothek)

Dieses Wechselverhältnis und der Umgang damit stellen ein wesentliches und dynamisches Innovationsfeld für Bibliotheken dar. Kenntnisse der Funktionsweisen und der rechtlichen Implikationen des Digitalen auszubauen, ist für Bibliotheken eine Grundvoraussetzung für eine verantwortungsvolle und rechtskonforme Bereitstellung von Informationen. Gleichzeitig gilt es, die gesellschaftlichen Folgen der zunehmenden Präsenz des Digitalen reflektiert zu beobachten. Nur so können neue Anforderungen der Informationsvermittlung und der Vermittlung von digitaler Kompetenz erfüllt werden.

Da Kundinnen und Kunden von Bibliotheken zunehmend nicht nur im Rahmen wissenschaftlicher Publikationen, sondern auch in sozialen privaten und beruflichen Netzwerken zu Produzenten von Information werden, können und sollten sich Bibliotheken jenseits der klassischen Vermittlung von Informationskompetenz auch in diesem Feld beratend positionieren. Sie können auf der Grundlage fundierter technischer und rechtlicher Kenntnisse und im Wissen um die grossen Mehrwerte des Digitalen geeignete Wege des verantwortungsvollen Umgangs auch mit privaten Daten aufzeigen.

Konkret können Bibliotheken beispielsweise Studierende im sinnvollen Umgang mit der Erstellung von Selbstprofilen auf Karriereplattformen und der bestmöglichen Synchronisation von Daten auf verschiedenen Plattformen beraten. Auch können sie z.B. Orientierungshilfe bei der Nutzung von digitalen Identifikatoren, wie z.B. ORCID, bieten. Dabei sollten Bibliotheken – auch in Kooperation mit Informatik- und Rechtsdiensten an Hochschulen – verstärkt auf die rechtlichen Grundlagen des Datenschutzes und dessen Gefährdung in verschiedenen Kontexten hinweisen und möglichst konkrete Handlungsoptionen für die Nutzerinnen und Nutzer aufzeigen.

Das Spannungsverhältnis von Informationsfreiheit und Datenschutz bzw. Privatsphäre bringt im digitalen Kontext immer neue Herausforderungen für die Gesellschaft mit sich, aus denen Innovationsfelder entstehen. Ausgehend von konkreten Handlungsfeldern der Nutzerinnen und Nutzer können Bibliotheken wie auch andere Infrastruktureinrichtungen informierte Umgangsformen mit dem allgegenwärtigen Spannungsverhältnis von Informationsfreiheit und Privatsphäre entwickeln. Jenseits der konkreten Informationsversorgung wäre es wünschenswert, dass Bibliotheken hierbei auch eine gesellschaftspolitische Rolle übernehmen und sich als Akteur in die Gestaltung dieses Felds einbringen.

Dieses Werk unterliegt einer Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License.

![]() [:en]In October 2014 the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade was awarded to Jaron Lanier, an American computer scientist, musician and author. The Jury’s reasoning: “Jaron Lanier highlights the threats to our open society when it is deprived of the power of control and when people, despite gaining variety and freedom, are reduced to digital categories.”

[:en]In October 2014 the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade was awarded to Jaron Lanier, an American computer scientist, musician and author. The Jury’s reasoning: “Jaron Lanier highlights the threats to our open society when it is deprived of the power of control and when people, despite gaining variety and freedom, are reduced to digital categories.”

In December 2014 Edward Snowden, the former American CIA employee, received the Right Livelihood Award “[…] for his courage and skill in revealing the unprecedented extent of state surveillance violating basic democratic processes and constitutional rights”.

And in May 2014 the European Court of Justice decided that, in the interests of data protection, search engine operators would be obligated to remove certain websites from their search results in order to preserve the so-called right to be forgotten with regard to sensitive personal data. To date, Google has received a total of 205,724 requests to delete websites throughout Europe. Google examined 747,832 websites and removed 40.4 per cent of them. Social networks and other search services were particularly affected by the deletions. The ruling was essentially well received. Critics, however, point out that the public interest in certain people might be heavily restricted by the ruling and therefore every deletion needs to undergo a thorough assessment by experts..

These high-profile examples of the presence of the digital sphere just go to show that the possibilities and limitations of the digital universe have already left their mark on a wide variety of sub-areas of our society. They also particularly reveal that threats to both individuals and society can emanate from the ways in which the digital world works. Besides more flexibility, an uninterrupted supply of information, mobile spatial navigation, and professional and private networking via social media channels also potentially provide more transparency about individual activities. Private data is re-used commercially and the power over contents once they have been rendered publicly accessible on the web often lies – at least until the ruling of the European Court of Justice in May 2014 – totally beyond the control of the person the data concerns. In his highly impressive work entitled Transparenzgesellschaft (Matthes & Seitz 2012, p. 76f), philosopher Byung-Chul Han points out that new forms of control are becoming possible in the digital society through the voluntary surrender of the private and intimate sphere, and the transparency that this entails.

Despite these developments and insights, the awareness that the digital world – in its current form – is to be regarded as quasi “public” and a certain degree of self-initiative and additional effort is necessary to protect one’s own private sphere is only growing gradually. All too often, personal data is shared unreservedly for largely uncontrolled re-usage – e.g. by agreeing to data privacy terms that have not been read or making data publicly accessible on social networks. In the process, the protection of private data that is worth protecting often comes up short.

Image 1: Sayings of DonkeyHotey #002, Flickr, CC-BY-2.0

The presence of the digital world – especially in its positive and expansive possibilities – has also left its mark on the work of academic libraries. Publications and research data based on publications, for instance, are increasingly being provided digitally and thus rendered re-usable for various contexts. Moreover, libraries and their customers also largely move in the digital environment.

Consequently, interfaces and cross-system functions of digital authentication and authorisation are becoming increasingly important. This is because they actually make it technically possible to guarantee comprehensive, seamless access to information. Libraries, whose role it is to explore technical solutions in this field, increasingly move in the tense relationship between two equally important fundamental rights: freedom of information and the protection of the private sphere.

Image 2: Examples of digital usage scenarios where academic libraries offer Support

This interrelationship and its handling constitute a major and dynamic innovation field for libraries. For the latter, a better understanding of the way the digital world works and the legal implications is a basic requirement for a responsible and legally compliant provision of information. At the same time, the social consequences of the mounting presence of the digital world needs to be observed with reflection. Only thus can new requirements for the mediation of information and digital competence be met.

As library customers are increasingly becoming producers of information, not just within the scope of academic papers, but also in private and professional social networks, libraries can and should also assume an advisory role in this field above and beyond the classical mediation of information literacy. Based on well-founded technical and legal knowhow and in the knowledge of the major added value of the digital world, they can also highlight suitable ways to handle private data responsibly.

In concrete terms, libraries can advise students on how to handle the creation of their own profiles on careers platforms sensibly and synchronise data on different platforms in the best possible way. They can also offer guidance on the use of digital identifiers, such as ORCID. In doing so, libraries should – including in collaboration with IT and legal services at universities – increasingly highlight the legal bases of data protection and the threats to it in different contexts, and, if possible, point out concrete courses of action open to users.

In the digital context, the tense relationship between freedom of information and data protection and the private sphere keeps posing fresh challenges for society, which give rise to innovation fields. Based on concrete fields of action on the part of the users, libraries and other infrastructural facilities are able to develop informed ways of dealing with this ubiquitous tense relationship. Beyond the concrete information supply, it would be preferable for libraries to also assume a socio-political role here and play an active role in shaping this field.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License.

![]() [:]

[:]